Irrationality

Hi! I’m Laurel, a brand strategist at Addis Creson.

I’ll be taking you through a Coursera online class, “A Beginner’s Guide to Irrational Behavior.” Throughout the six-week series, I’ll summarize key points that are relevant to the brand strategy discipline.

Dan Ariely is a professor of Psychology and Behavioral Economics at Duke University. His bestselling 2008 book, Predictably Irrational, presents the idea that previously ignored or misunderstood forces, such as emotions, environment, memories, and context, influence our decisions more than we think. We have an illusion of agency—we believe we are fully aware of all the reasons behind our actions. However, Ariely argues our decisions can be highly sensitive to situational factors and we are relatively insensitive to the impact of these factors. This argument holds that we misattribute behaviors affected by these factors to stable underlying preferences and, in turn, create stories to justify and explain our actions.

The example Ariely uses to illustrate this point is organ donation rates in European countries. Why do the Netherlands and Belgium—neighboring countries— have radically different organ donation rates? Most people attribute it to cultural differences or personal beliefs. In reality, it’s the design of the donation form. In the Netherlands, where people opt in to donate, participation rates hover around 28% despite massive awareness campaigns. Conversely, in Belgium, citizens must opt out, and their country boasts a 98% participation rate. This illustrates that the human norm is to take the path of least resistance. We don’t usually attribute our decisions to the context of the experience—in this case, the design of the organ donation form.

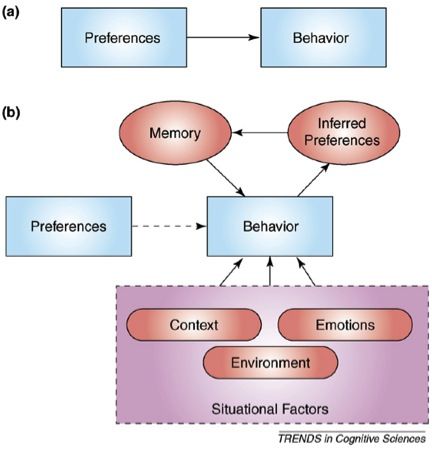

The chart below from Ariely & Norton’s article “How actions create – not just reveal – preferences.” Trends in Cognitive Science. 12(1) 2008, illustrates the factors at play when making a decision. It demonstrates that we think our decision making process is guided by consciously known, rational preferences (a). In reality, it’s more complicated than we realize. More is going on beneath the surface, and the full picture often does not match our rationalization (b).

Following this theory, Ariely proposes that focus groups are particularly uninformative because participants cannot articulate the full scope of why they do what they do. He argues that participant observation approaches (like ethnographic research) reveal more useful data. That is, Ariely’s theory holds that observational research is better suited to reveal the motivations behind behaviors, whereas focus groups reveal abstracted explanations of behaviors, which lead to distorted data.

The argument for or against focus groups is a point of contention in our industry. We’ve certainly sat through dozens of focus groups that didn’t reveal much in the way of breakthrough insights. However, when done well, focus groups can be an efficient and effective tool to stimulate discussion. However, findings from such sessions are directional and need to be used carefully.

In our own work, we have achieved excellent results from a more natural and engaging style of qualitative group inquiry. Whether the topic is new brand creation, culture building, sustainability, or strategy, we follow three inquiry design guidelines to reveal insights that lead to our clients’ success.

1. We choose an engaging environment appropriate to the research context.

2. We design interactive activities that allow individuals and groups to engage multiple ways of knowing.

3. We employ facilitators who are highly empathetic, adaptive, and imaginative.

Our philosophy is based in the belief that when we come together as a community of inquiry, we are able to create new knowledge and, in turn, design new futures.